Abstract

Post-extubation stridor is a well-recognized complication following endotracheal intubation and is most commonly attributed to laryngeal edema, vocal cord dysfunction, or subglottic stenosis. However, delayed onset stridor occurring several days after extubation is unusual and warrants evaluation for less common etiologies. Tracheal mucosal flap formation is a rare but important cause of delayed post-extubation airway obstruction. We describe a case of a 70-year-old male who developed inspiratory stridor three days after extubation, in whom video laryngoscopy revealed a tracheal mucosal flap. The patient was managed conservatively with systemic corticosteroids, nebulized therapy and positive pressure ventilation resulting in complete resolution on repeat endoscopy. This article reviews the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and management of tracheal mucosal flap as a delayed cause of post-extubation stridor.

Introduction

Endotracheal intubation is a life-saving intervention frequently performed in emergency and critical care settings. Despite advances in airway equipment and techniques, airway-related complications remain common, particularly in elderly and critically ill patients. Post-extubation stridor occurs in approximately 2–16% of extubated patients and is traditionally associated with laryngeal edema, vocal cord paresis, granuloma formation, or subglottic stenosis.

Most cases of post-extubation stridor present within hours of extubation. Delayed onset stridor—developing days after extubation—is uncommon and often misattributed to pulmonary or infectious causes. Tracheal mucosal flap formation represents a rare and under-recognized etiology of delayed airway obstruction following intubation. Awareness of this entity is crucial, as early recognition can prevent unnecessary reintubation and invasive airway interventions.

Case Description

A 70-year-old male with no known prior airway disease presented to the emergency department with altered sensorium. Initial evaluation revealed severe hyperglycemia with hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, secondary to a urinary tract infection. The patient required endotracheal intubation in the emergency room for airway protection due to reduced consciousness.

Intubation was reportedly uneventful, and mechanical ventilation was continued for 48 hours. The patient improved with appropriate fluid resuscitation, insulin therapy, and antibiotics, and was successfully extubated on day 2 of admission. Post-extubation, he remained stable with no immediate respiratory distress or voice change.

On the third day following extubation, the patient developed progressive inspiratory stridor, more pronounced during exertion and while supine. There was no fever, cough, or signs of aspiration. Oxygen saturation remained within the normal range, but audible stridor prompted airway evaluation.

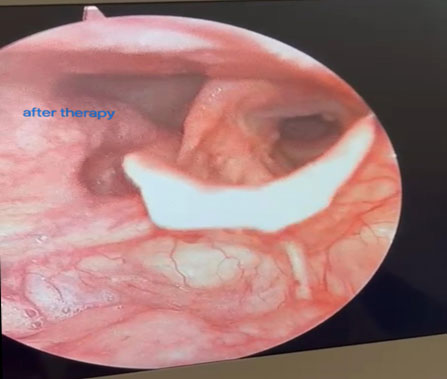

Video laryngoscopy revealed a mobile mucosal flap arising from the tracheal mucosa, intermittently prolapsing into the airway lumen during inspiration. There was no significant vocal cord edema or paralysis. Given the absence of severe respiratory compromise, the patient was managed conservatively with systemic and nebulized corticosteroids, bronchodilators and positive pressure ventilation.

Over the next week, the patient’s stridor gradually resolved. Repeat video laryngoscopy after seven days demonstrated complete resolution of the mucosal flap, with normal airway patency. The patient had no recurrence of symptoms on follow-up.

Pathophysiology of Tracheal Mucosal Flap Formation

The tracheal mucosa is composed of pseudostratified ciliated epithelium overlying a delicate submucosal layer. Endotracheal intubation can cause varying degrees of mucosal injury due to:

Mechanical trauma during tube insertion

Friction between the tube and tracheal wall

Excessive cuff pressure leading to ischemia

Repeated micro-movements of the tube with coughing or repositioning

In elderly patients, age-related mucosal fragility and impaired tissue repair increases the susceptibility to injury. Systemic factors such as dehydration, sepsis, hyperglycemia, and poor perfusion further compromise mucosal integrity.

A tracheal mucosal flap likely forms when partial-thickness mucosal injury occurs, resulting in a loose segment of mucosa that remains attached at one end. During inspiration, negative intrathoracic pressure draws the flap into the airway lumen, producing dynamic obstruction and stridor. This mechanism explains the delayed onset of symptoms, as inflammation and edema evolve over several days following extubation.

Clinical Presentation

Key clinical features include:

Delayed onset stridor, typically 2–7 days post-extubation

Predominantly inspiratory stridor

Symptoms exacerbated by exertion or supine position

Minimal response to bronchodilators

Preserved oxygenation in mild to moderate cases

Unlike laryngeal edema, voice changes and dysphonia are often absent. The intermittent nature of obstruction may lead to underestimation of severity.

Differential Diagnosis of Delayed Post-Extubation Stridor

Delayed stridor necessitates consideration of uncommon etiologies:

Tracheal mucosal flap

Tracheal ulceration or pseudomembrane

Post-intubation tracheal stenosis

Granuloma formation

Vocal cord dysfunction

Tracheomalacia

Infectious tracheitis

Distinguishing among these conditions requires direct airway visualization.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Flexible or video laryngoscopy is the diagnostic modality of choice. It allows dynamic assessment of the airway and visualization of mobile lesions such as mucosal flaps. Bronchoscopy may be required if the lesion is distal or if diagnosis remains uncertain.

Computed tomography of the neck and chest may assist in excluding extrinsic compression or fixed stenotic lesions but is less sensitive for dynamic mucosal abnormalities.

Management Strategies

Conservative Management

Most cases of tracheal mucosal flap without significant airway compromise can be managed conservatively:

Systemic corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and edema

Nebulized corticosteroids and bronchodilators

Humidified oxygen

Voice rest and avoidance of coughing

Close monitoring is essential, particularly in elderly patients.

Interventional Management

In cases with severe obstruction or progressive respiratory distress:

Bronchoscopic trimming or removal of the flap

Temporary airway stenting

Reintubation or tracheostomy (rarely required)

Early ENT and pulmonology involvement is recommended.

Outcome and Prognosis

With timely recognition and appropriate management, the prognosis is excellent. Most mucosal flaps resolve completely within days to weeks as epithelial healing occurs. Long-term sequelae are uncommon.

Discussion

This case highlights several important learning points. First, post-extubation stridor is not always immediate and benign. Second, elderly patients with metabolic derangements are at increased risk for airway mucosal injury. Third, conservative management can be effective when diagnosis is made early.

Tracheal mucosal flap formation remains under-reported, possibly due to lack of routine endoscopic evaluation in delayed stridor. Increased awareness among intensivists and emergency physicians can prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary invasive airway interventions.

Conclusion

Tracheal mucosal flap is a rare but important cause of delayed post-extubation stridor. Clinicians should consider this diagnosis in patients presenting with stridor several days after extubation, particularly when common causes have been excluded. Early airway visualization and conservative therapy can lead to complete resolution and excellent outcomes.

References

Esteller-More E, Ibañez J, Matiñó E, Quer IM. Prognostic factors in post-intubation laryngeal edema. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(11):880-883.

Colice GL, Stukel TA, Dain B. Laryngeal complications of prolonged intubation. Chest. 1989;96(4):877-884.

Kastanos N, Estopá Miró R, Marín Perez A, Xaubet Mir A, Agustí Vidal A. Laryngotracheal injury due to endotracheal intubation. Chest. 1983;84(3):341-345.

Benjamin B. Prolonged intubation injuries of the larynx: Endoscopic diagnosis, classification, and treatment. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102(6):430-437.

Pluijms WA, van Mook WN, Wittekamp BH, Bergmans DC. Postextubation laryngeal edema and stridor resulting in respiratory failure in critically ill adult patients. Crit Care. 2015;19:295.

Stauffer JL, Olson DE, Petty TL. Complications and consequences of endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy. Am J Med. 1981;70(1):65-76.

Authors

Dr Ramapriya S

DrNB Post Graduate,

Critical Care Medicine,

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai.[1]

Dr Muralidharan

Consultant Critical Care Medicine

Kauvery Hospital, Chennai.[1]