Empowering Patients in Patient Care – Prevention of Medication Error

RN Gowdham. P

Nurse Educator, Kauvery Hospital, Marathahalli

Background

Promoting health safety in healthcare settings is a global challenge, with an estimated one in ten patients being harmed whilst receiving care.” Error is an inaccurate or incorrect action, thought, or judgement. Error is common and acceptable mistake which can be changed or corrected. But error in the field of medicine is unacceptable, as an error in our field will bring a terrific change in human life as well as in their entire family.

Medication error is one of the basic problems of health systems all over the world, which can be a serious threat to the safety of patients. Medication errors can lead to unpleasant consequences such as prolonged hospitalization, increased treatment costs and even death. There are many easily correctable ways in how these errors occur, little things that could be changed to stop them, but they still happen. We will be discussing a variety of occurrences that bring about these errors and what are some interventions that can be done to prevent more of them from taking place.

Statistical Data of Medication Error

While searching for errors that have occurred with medications, I am alarmed to see the data. Globally the cost associated with medication errors has been estimated at $42 billion USD annually. In the United States alone 7,000 to 9,000 people die of a medication error. Additionally, hundreds of thousands of other patients experience but often do not report an adverse reaction or other medication complications. The total cost of looking after patients with medication-associated errors exceeds $40 billion each year. Medication error is the third leading cause of death in America.

The results of a survey conducted in 2018 in the UK found that more than 2 million people are affected by the complications of medication error every year and give rise to death almost 100 thousand people.

According to a recent finding, in India the incidence of medication error was as high as 82/1,000 prescriptions in Delhi, and the national figures report up to 5.2 million medical errors annually. Studies done in Uttarakhand and Karnataka have documented medication error rate to be as high as 25.7% and 15.34%, respectively, in hospitalized patients.

In Tamil Nadu, A study was conducted over the period of one year at a tertiary care teaching hospital and that over all percentage of medication error observed was 42.5% with 81.08% prescribing error and 18.91% administrative errors.

Unfortunately, most of the medication error remain undetected, if clinical significance or outcome does not adversely affect the patient.

Medication Error

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP) has defined medication errors as, “Any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm, while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer.”

Medication error refers to any malpractice in the medication process (prescribing, preparing and administering), regardless of whether it has side effects for the patient or not, which can occur at any stage of the drug therapy cycle from prescription, transcription, distribution to drug administration.

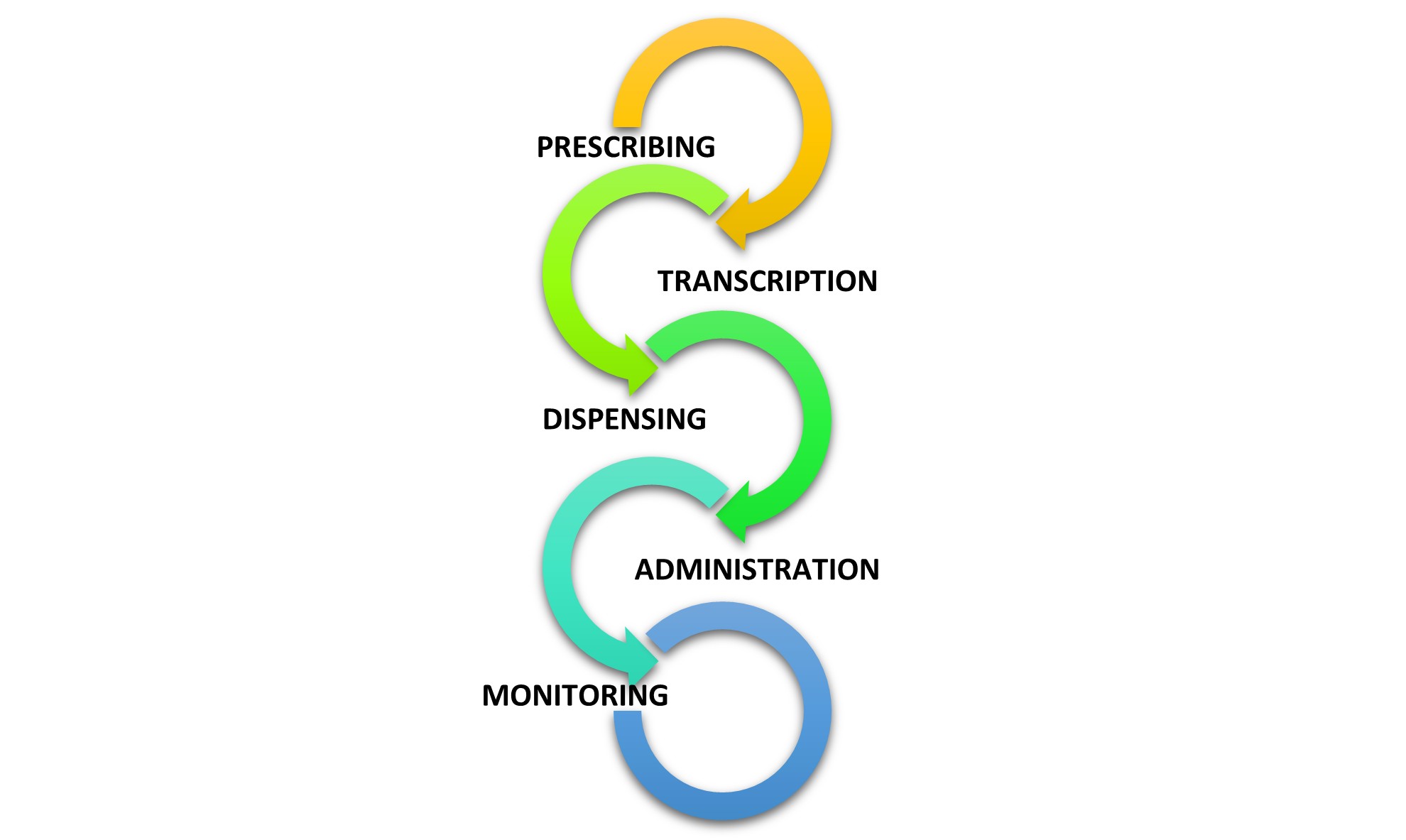

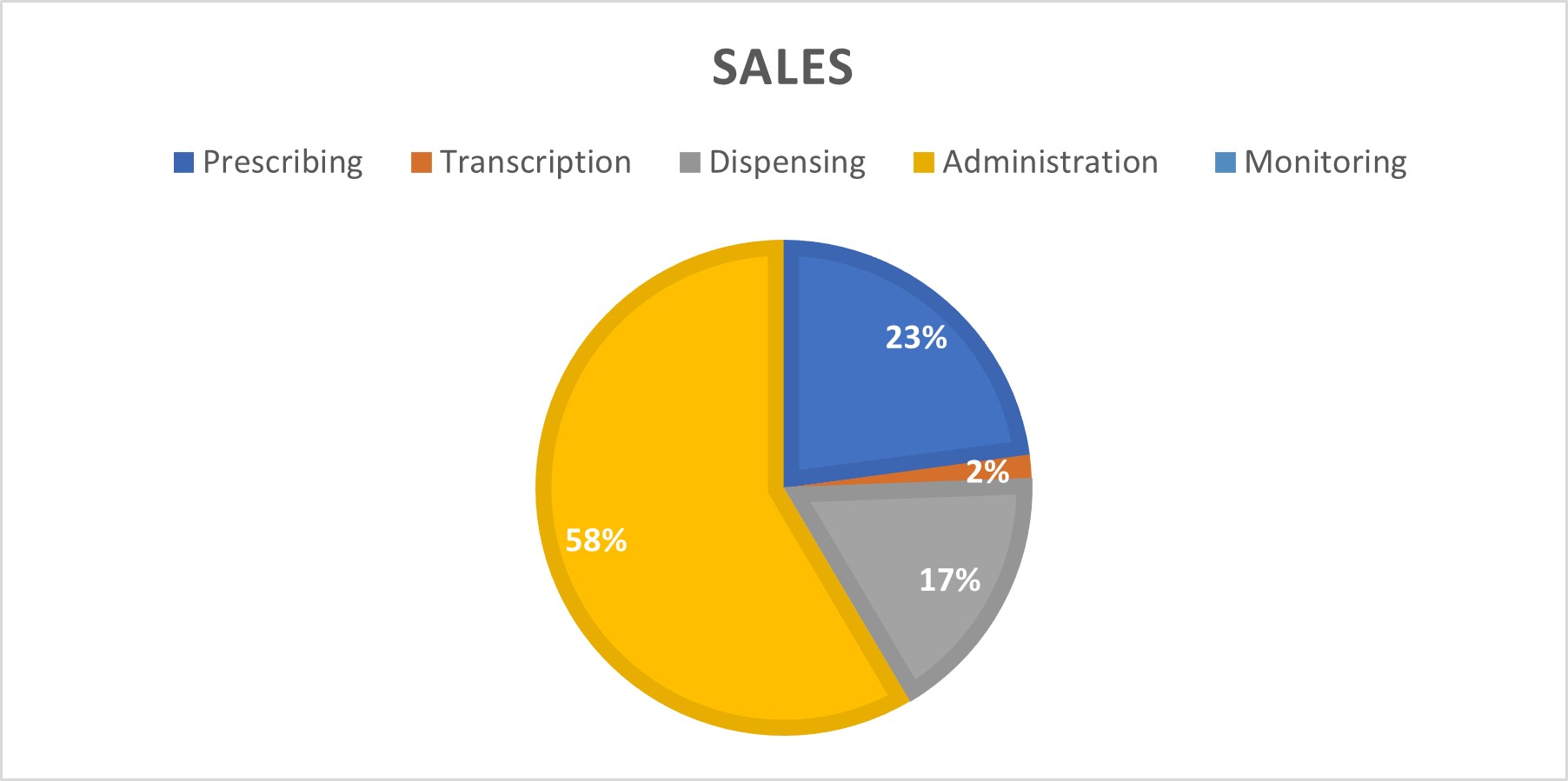

According to WHO, Medication error occurs in following stages

Prescribing (21.3%), transcription (1.4%), dispensing (15.9%), administration (54.4%) and monitoring (7.0%).

However, previous studies have shown that most errors occur when the medication is delivered to the patient. Doctors’ prescriptions, nurses’ implementation of drug orders, pharmacists’ reading of prescriptions in pharmacies, and sometimes patients themselves and their families play a role in medication errors. Evidence suggests that all, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, patients and patient’s family members are involved in such errors.

Factors contributing medication error

Medication Error Specifically Due To Patient

| Provider | Patients |

|---|---|

| Overwork in workplace | In a hurry |

| Undertrained | Health literacy level |

| Lack of competence | Improper education regarding medication |

| Distracted | Dose, time, etc. |

| Illness | — |

| Stress | — |

A study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society in 2007 outlined six categories of patient medication errors:

- Medication filling and refilling errors

- Medication administration errors

- Failure to perform some parts of the medication regimen

- Failure to follow clinical advice

- Failure to report information to providers

- Failure to adhere to follow-up

During medication administration, there is about 8% – 25% median medication error rate (Patient Safety Network, 2018). Medication errors in the home are estimated to occur at rates between 2%-33% (Patient Safety Network, 2018).

Statistical Evidence for Patients’ Medication Error

1 in 5 adverse drug events caused by error were related to patient use of medications at home (The Journal of the American Medical Association, 2003). Dosage errors are the most common type of medication administration errors. 7.8% of carers reported giving an insufficient dose, 6.6% reported giving an overdose, and 5.4% reported giving the wrong medication (PLOS One, 2016).

Solutions To Regulate Medication Error

Patient Education

Health care professionals must provide adequate patient education about the appropriate use of their medications as part of any error prevention program. Proper education empowers the patient to participate in their health care and safeguard against errors. Some examples of instructions to patients that can help prevent medication errors are:

- Know the names and indications of your medications

- Read the medication information sheet provided by your pharmacists

- Do not share your medications

- Check the expiration date of your medications and dispose of expired drugs

- Learn about proper drug storage

- Keep medication out of the reach of children

- Learn about potential drug interactions and warnings

The responsibility for the prevention of medical errors rests not only with health care professionals and health care systems but also with the patients themselves. By being informed not only about the names of their medications but the reasons for their use, the times they should be administered and the correct dose, patients can act as the final check in the system. The practice of carrying a continually updated list of medications can be invaluable in the event of an emergency or if patients cannot speak for themselves. This reduces the chance of miscommunication or misinformation. When patients take an active and informed role in his or her health, many errors can be prevented.

Prior Authorization

Prior authorization programs are used by managed health care systems as a tool to assist in providing quality, cost-effective prescription drug benefits. Improving patient safety by promoting appropriate drug use is an integral function of prior authorization programs. Medication errors can be reduced by prior authorization systems in various ways. First, a health plan may limit coverage to FDA-approved uses as well as unapproved uses that are substantiated by appropriate and adequate medical evidence. Prior authorization may be used to protect against adverse events in highly contraindicated populations. For example, prior approval should be required for Accutane® to ensure that no pregnant women receive this medication because it has a high incidence of causing birth defects. A prior authorization program may also be employed to ensure that patients do not receive certain drugs, such as antibiotics, for exceedingly long durations that could put patients at increased risk for adverse events. Overall, a well-designed prior authorization program is a useful tool in promoting patient safety and reducing medication errors.

Bar Coding

One way in which electronic technology can improve patient safety and reduce medication errors is by standard machine-readable codes (“bar codes”). Medication bar coding is a tool that can help ensure that the right medication and the right dose are administered to the right patient. Today’s technology embeds increasing amounts of information within a scannable bar code on even the smallest packages. The NCCMERP recommends that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and pharmaceutical manufacturers collaborate to have the following information imbedded into a medication bar code.

- National Drug Code (NDC) number which identifies the unique drug, dosage form, and strength.

- Lot/Control/Batch number, which assists in cases of product recalls.

- Expiration date, which helps to ensure that patients do not receive expired medications

Electronic Prescription Record

An electronic prescription record (EPR) contains all the data legally required to fill, label, dispense and/or submit a payment request for a prescription. Pharmacists use the record as a tool to reduce medication errors by guarding against drug interactions, duplicate therapy and drug contraindications. The EPR can also help reduce medication errors by helping pharmacists monitor and audit utilization and by facilitating communication between health care providers to improve patient care.

E-prescribing Utilization of electronic prescribing by entering orders on a computer, better known as Computerized Physician Order Entry (CPOE), is a technology that could help prevent many medication errors. CPOE systems allow physicians to enter prescription orders into a computer or other device directly, thus eliminating or significantly reducing the need for handwritten orders. E-prescribing and CPOE can reduce medication errors by eliminating illegible and poorly handwritten prescriptions, ensuring proper terminology and abbreviations, and preventing ambiguous orders and omitted information. More advanced CPOE software incorporates additional safety features that allow the physician to have access to accurate patient information, including patient demographic information such as age, medication history and medication allergies.

Electronic DUR

Due to the technology of the electronic prescription record, pharmacists can conduct prospective online drug utilization reviews (DUR). The online DUR process allows the pharmacist to conduct a review of the prescription order at the time it is presented for filling and proactively resolving potential drug-patient problems such as drug-drug interactions, over-use, under-use and medication allergies. This technology allows the pharmacist to assess the prescription order at the time of dispensing and, using information from the patient’s medical and/or pharmacy record, determine the appropriateness of the prescribed medication therapy. Medication safety issues commonly addressed in an online DUR process include the following:

- Drug-disease contraindications

- Drug-drug interactions

- Incorrect drug dosage

- Inappropriate duration of drug treatment

- Drug-allergy interactions

- Clinical abuse or misuse

Automated Medication Dispensing

Automated medication dispensing systems are now widely used as a less labor-intensive method of dispensing medications. Automated pharmacy dispensing systems are more efficient at performing pharmacists’ tasks that require tedious, repetitive motions, high concentration and reliable record keeping, which can all lead to medication dispensing errors. When utilized appropriately, automated medication dispensing systems help to reduce medication errors and improve patient safety. Many automated dispensing systems utilize the bar-coding technology discussed earlier to ensure the right drug, dose and dosage form is used.

Internal Quality Control Procedures

Most medication dispensing settings have developed quality evaluation procedures. These practices provide workflow evaluation and error reporting analyses, which lead to excellent protection from medication error.

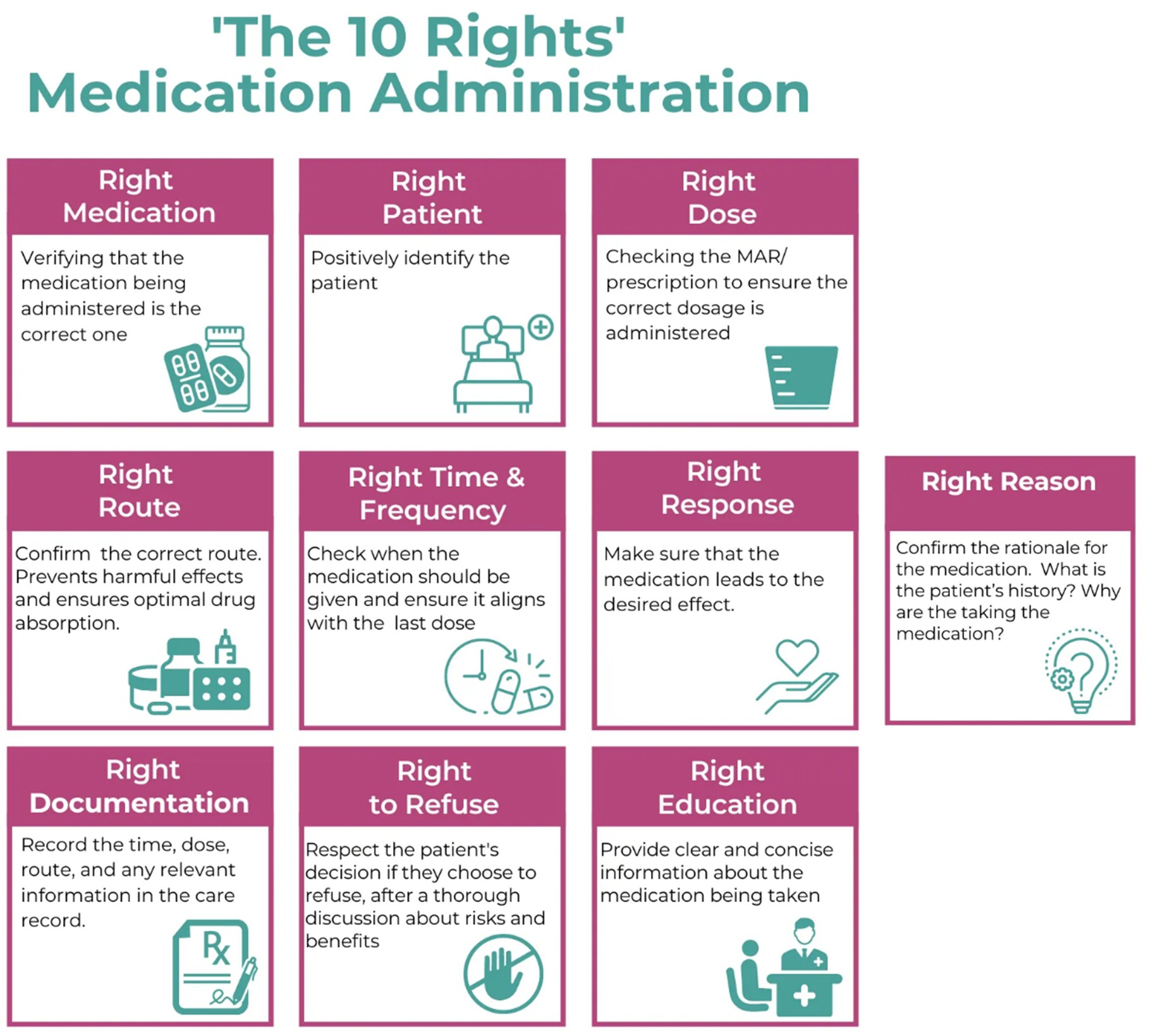

For which WHO approved the concept of 10 Rights of medication

Now, 4 core concept framework has been created by WHO which is more effective in hospital as well as patient side.

High-risk situations: understanding situations where evidence shows that there is a higher risk of harm from certain medications is key. Tools and technologies may help health-care professionals who use high-alert medications and enhance patient knowledge and understanding of these medications.

Polypharmacy: the standardization of policies, procedures and protocols is critical in the case of polypharmacy. This is applicable from initial prescribing practices to regular medication reviews. Technology can also serve as a useful aid by enhancing patient awareness and knowledge about the medication use process.

Transition of care: transition of care increases the possibility of communication errors, which can lead to serious MEs. Good communication is vital, including a formal comparison of medicines pre- and post-care, so-called medication reconciliation.

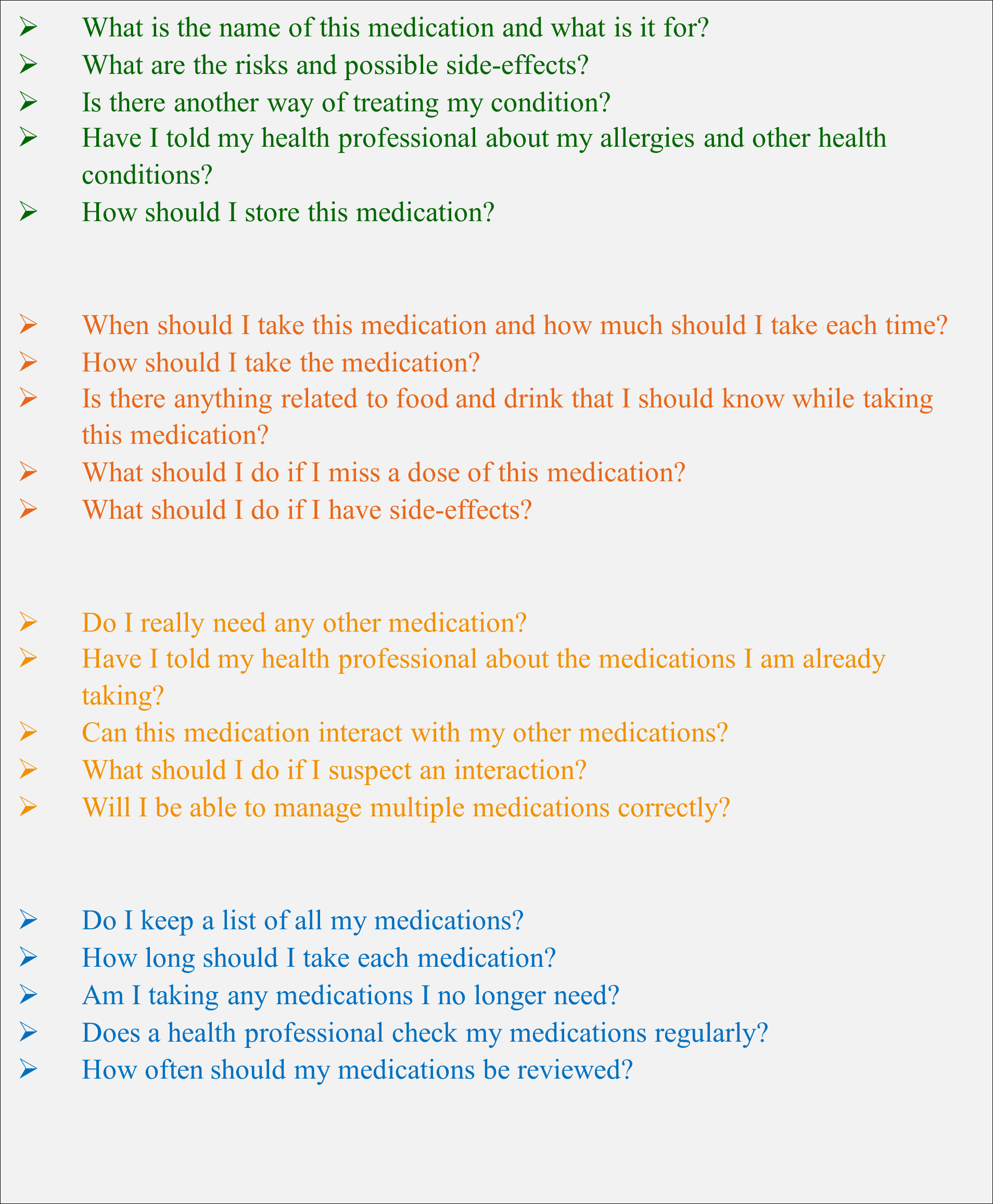

Patient Engagement Tool: “5 Moments for Medication Safety” By Ms Nagwa Metwally, Ms Helen Haskell

To engage patients, we must engage the health care workers

| Barriers To Patient Engagement | |

|---|---|

| Doctor | • Too little time to discuss medications with patients. • Patients often uninformed about risks, side effects, or when to stop medications. • May not ask about other medicines the patient is taking. • Risk of addiction or fatal errors if not well explained. • Bad handwriting can lead to misunderstandings. • Low patient literacy. • Lack of follow-up on medication effectiveness or adverse events. • Poor documentation in medical records. |

| Nurse | • Often not trained or expected to engage patients effectively. • Engagement hindered by heavy workloads. • Lack of ongoing medication safety training. • Inadequate supervision and accountability. • Systemic risks like look-alike, sound-alike drugs. • Overloaded nurses may administer incorrect medications. • Patients may lack knowledge to identify errors. |

| Pharmacist | • Community pharmacists often used instead of doctors due to cost or access. • Dispensing medications without prescription is common. • Unqualified assistants may run pharmacies unsupervised. • No coordination with doctors regarding unprescribed medications. |

| Hospital Administrator | • Patients unaware of risks like improper drug storage or high-risk medications not separated. • Wrong dosages may be dispensed. • Shortage of hospital pharmacists means no review before discharge. • Poorly coordinated care—patients left to manage medications alone. • Inadequate systems for reporting medication errors and adverse events. |

Patient factors contributing to medication safety issues

- Illiteracy/poor education

o Uneducated patients cannot read labels, expiry dates, instructions, doctors’ handwriting

- Low income

o Leads to depending on pharmacists for health care

- Complete trust in doctors and nurses as authorities

- Lack of knowledge about their medications

- Reluctance to ask questions

o Patients do not know what to ask

o Doctor may not be receptive to questions

- Difficulty of reporting errors and adverse events

o No clear reporting channel

o Patients don’t know how to report

o Patients do not trust that reporting will have an effect

Patient engagement: Possible solutions for health care providers

Ask governments and hospitals to

- Develop patient champions in hospitals

- Train health care providers on how to talk to patients

o How to use plain language

o What to tell patients

o What to ask patients

- Improve regulation of medications and pharmacies

- Improve coordination of dispensing and supervision of nurses

- It’s all about training, supervision, and prevention of errors. This will give confidence to patients.

5 Moments For Medication Safety

Goal

Raise awareness among patients for the need to take precautions to ensure medication safety.

Conclusion

Medication errors should be seen as opportunities to assess practice, find out what went wrong, learn from mistakes, and make changes. We must accept that they happen and do what we can do to stop them from occurring, but we can also see them in a beneficial way. It is a practice and learning opportunity, and we should use it to our advantage. As we can see from the differing preventions that can be made, they are not difficult, they just need to be done. In all the healthcare settings we can put effort into making patients and patient relatives more aware of these little preventions and helping to make them matter more. If we contribute from our part, we can really help patients receive safer medication treatments.

REFERENCE

- Wittich CM, Burkle CM, Lanier WL. Medication errors: an overview for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Aug;89(8):1116-25.

- Whittaker CF, Miklich MA, Patel RS, Fink JC. Medication Safety Principles and Practice among patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Nov 07;13(11):1738-1746.

- Ibrahim OM, Ibrahim RM, Meslamani AZA, Mazrouei NA. Dispensing errors in community pharmacies in the United Arab Emirates: investigating incidence, types, severity, and causes. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2020 Oct-Dec;18(4):2111.

- Zirpe KG, Seta B, Gholap S, Aurangabadi K, Gurav SK, Deshmukh AM, Wankhede P, Suryawanshi P, Vasanth S, Kurian M, Philip E, Jagtap N, Pandit E. Incidence of Medication Error in Critical Care Unit of a Tertiary Care Hospital: Where Do We Stand? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020 Sep;24(9):799-803.

- Sim MA, Ti LK, Mujumdar S, Chew STH, Penanueva DJB, Kumar BM, Ang SBL. Sustaining the Gains: A 7-Year Follow-Through of a Hospital-Wide Patient Safety Improvement Project on Hospital-Wide Adverse Event Outcomes and Patient Safety Culture. J Patient Saf. 2022 Jan 01;18(1):e189-e195.

- Aseeri M, Banasser G, Baduhduh O, Baksh S, Ghalibi N. Evaluation of Medication Error Incident Reports at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020 Apr 19;8(2)

- Neal JM, Neal EJ, Weinberg GL. American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity checklist: 2020 version. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021 Jan;46(1):81-82.

- Kefale B, Degu A, Tegegne GT. Medication-related problems and adverse drug reactions in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020 Oct;8(5):e00641.

- Gonzaga de Andrade Santos TN, Mendonça da Cruz Macieira G, Cardoso Sodré Alves BM, Onozato T, Cunha Cardoso G, Ferreira Nascimento MT, Saquete Martins-Filho PR, Pereira de Lyra D, Oliveira Filho AD. Prevalence of clinically manifested drug interactions in hospitalized patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235353.

- Uhlenhopp DJ, Aguilar O, Dai D, Ghosh A, Shaw M, Mitra C. Hospital-Wide Medication Reconciliation Program: Error Identification, Cost-Effectiveness, and Detecting High-Risk Individuals on Admission. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2020;9:195-203.

- https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/patient-safety/mwh-webinar